On the fifth Sunday of Lent, the Orthodox Church remembers the Venerable Mary of Egypt. The saint is famous for her decisive change of lifestyle: from a woman of easy virtue she became a Christian ascetic at the cost of an irrevocable break with civilization and an ascetic exploit. Why Orthodox Old Believers remember Mary of Egypt shortly before preparing for Easter - let's talk today.

For the ancient societies of the Middle East, where Christianity originated, women's premarital and extramarital sexual relations were interpreted unequivocally negatively, with possible consequences up to and including a national trial. The Jews, for example, stoned harlots to death. The society of tradition and law presupposed strict limits and exemplary punishments for the sake of social order. Fornication dealt a heavy blow to the institution of the family, and the weakness of the primary unit of society threatened its monolithic nature. The strength of ancient society was achieved through the observance of the social contract to uphold the laws of tradition. Individual freedoms and rights could be sacrificed to preserve social foundations.

Jesus Christ struck a devastating blow to this formula, not abandoning the fulfillment of the Mosaic law, but filling it with humanity in the full sense of the word. During his sermon, the Savior regularly appeals to the dormant conscience of the Jews, who, without thinking about the morality of their actions, do so because "it is the custom". The climax of the defense of humiliated and abused women in the Gospel is the episode of the rescue of a harlot from being stoned to death.

During a sermon in the Temple in Jerusalem, the Pharisees brought a woman who had been arrested for adultery to Christ. They were going to bring her to the people's justice, saying she had committed a sin. The Pharisees decided to ask Christ, as a respected preacher among the people, for an expert opinion on the trial (with the goal, however, of catching Him by the tongue, looking for a reason to condemn Him).

Jewish society was obviously already weighed down by the law, with its multiplicity and virtual unenforceability. The phenomenon of Jesus was his formula "So the Son of Man is Lord even of the Sabbath." (Mark 2:28). He explained to the people that the spiritual law was to help man to reveal his good nature, not to harm and become an impossible burden to fulfill. "Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." (John 8:7), Christ answered the question of the eager Jews.

The real nobility of mercy lies in the ability to forgive. It was one of the most important seeds of the Savior's teaching, and it germinated in successive generations of human civilization. State laws and international acts of human rights came out of Christian, deeply humanistic notions of morality and ethics. When the crowd, convicted by their own conscience, dispersed, the harlot was left alone with Christ. A short dialogue ensued between them. The Savior only asked, "Where are the harlot's accusers?" They scattered. Before the man of God stood the sinful woman, awaiting His judgment, as, according to Christian teaching, it will be at the end of human life. But Christ's judgment turned out to be highly merciful: He simply let the harlot go, asking her not to sin again.

The Venerable Mary of Egypt lived five centuries later than the Gospel events. At the age of 12, she ran away from her parents' home to Egyptian Alexandria, a major city and, as we would say now, one of the centers of world trade. It is unlikely that the girl was preoccupied with the fierce opposition between the growing power of the Copts and the aspiring Byzantines to order in the empire (including spiritual order). Surely Alexandria, like any metropolis, had many different levels of social life that did not overlap. While weaving baskets to support herself, Mary, drugged by the diversity of city life (she herself was obviously born and raised in the countryside), decided to live life to the fullest. Changing partners, noisy parties, male attention and adrenaline-endorphin storms became the meaning of life for the girl. Approaching the age mark of 30, Maria wanted to see the world. In keeping with her desire, a shipload of pilgrims was sailing for the Holy Land. Perhaps the ship was for charity, or maybe the woman understood that her body was the main coin with which to pay for almost everything.

Of course, Mary was not sailing to Jerusalem to worship shrines, but for a new experience. She was not at all interested in the approaching Feast of the Exaltation, but out of interest, once she was in the Holy City, she went with the pilgrims to the service. And here were the events that became the starting point for a change in Mary's life.

To begin with, the "pilgrim" was unable to enter the temple after four unsuccessful attempts. There were many people, and outwardly Maria just could not squeeze through the crowd. But before her eyes, other pilgrims made their way into the church through the narthex, and she, by her own admission, could not even cross the threshold. People can deny the mystical side of life for years and close themselves off from it in all kinds of ways. But one day, circumstances will come together in such a way that it will not be possible to shut them out. And she will have to answer a series of questions that have accumulated.

Mary was baptized. There is nothing surprising here: she lived in an environment for which Christianity had become a good tradition by the fifth century. People were baptized in infancy, but their inner choices were made independently much later. In Russia today, tens of millions of people call themselves baptized Orthodox. But self-determination is not always identical with the way of thinking and acting. Nevertheless, the environment lays down certain anchors, which at some point in life can manifest themselves. Mary realized that she could not fit into the unified temple organism because she was a completely alien element to it. But the temple, a holy place for Christians, reeked of joy and warmth. The spirit of God beckoned Mary to go inside, but she could not. She was destined to remain outside the confines of the feast of life alone with tons of inner impurity. She wept.

Thus Mary had her first conversation, first with her own conscience and then with Our Lady. After praying at the icon closest to her, the woman was able, in tears, to go inside and worship the Honest Tree, the relic on which Jesus Christ was crucified. Mary's heartache was so acute that she heard the voice of Our Lady. Our Lady promised the harlot that only in the Jordan wilderness, far away from the metropolis, people and destructive habits, could her soul be saved. Thus Mary, a young woman of thirty, took a step toward a lifelong spiritual marathon. She went to the desert to meet her real self, to get to know herself better, and to be able to cleanse herself from the plaque of sin that she had safely built up throughout her life.

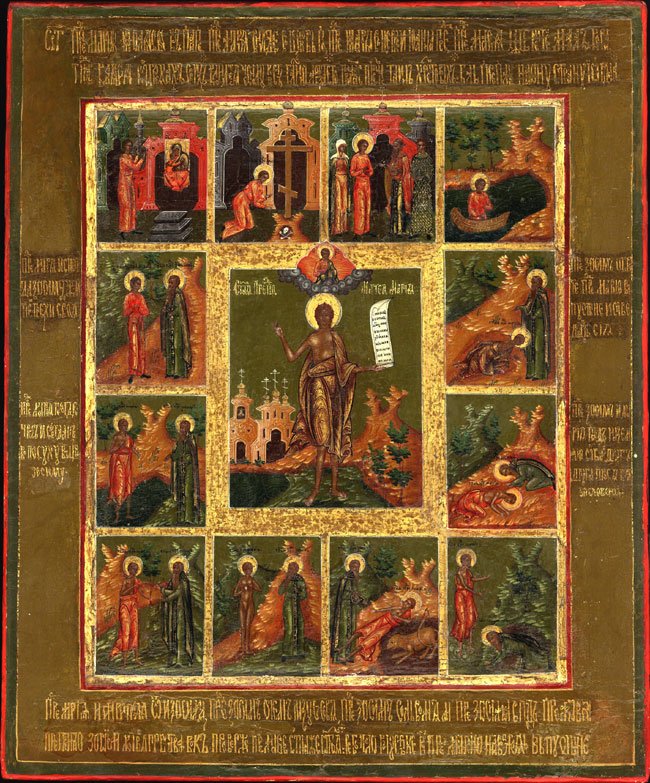

Mary spent 47 years of her life in the desert. It was a time of deprivation on the one hand, and purification on the other, that was the woman's price for entering the kingdom of heaven. She had to get rid of her habits and her former way of life by radical measures. Through prayer and fasting, penance, and seclusion, Mary achieved holiness, which in the last years of her life the old monk Zosima saw with his own eyes. The inhabitant of the monastery on the Jordan River, Zosima withdrew to the wilderness for the time of Great Lent to pray, hoping to meet the spiritually experienced hermit-elder. The monk met Mary.

The woman was in her seventies, her hair burned and her body blackened from the constant exposure to the scorching sun. Mary called herself a great sinner, but she knew the Scriptures well enough to float in the air and walk on water. Zosima came "to visit" Mary and a year later, having communed the saint with the Body and Blood of Christ, and another year later found her dead. The biography of the nun was carefully recorded from Zosima's account at his monastery, and very soon the harlot who had hidden herself from the world became known throughout the Orthodox Church. Moreover, her memory is dedicated to the fifth Sunday of Lent. In fact, this day becomes the last step before the direct preparation for Easter - Lazarus Saturday, Palm Sunday and Holy Week. But why Mary of Egypt and not any other of the thousands of Christian saints?

Jesus Christ noted that He did not come into the world of men for the righteous. Does a healthy person need help, or a wealthy businessman who is firmly established in life? I don't think so. Christ came to racketeers, paralyzed invalids, poor beggars, and repentant fallen women. God in human flesh came to those who needed Him. The mighty of this world were not waiting for Christ. They were doing well (as they thought). God came out of eternity into the world of time for those whose souls had a need for Him. The deeper a person's need for change was, the more the Savior resonated in their heart. Mary of Egypt was like that, closer than anyone else to all the people of the world.

Mary proved that every person, no matter how lost and despised they were from the point of view of human society, was important to God. "People don't change" is the harsh, categorical verdict of a society wise by "experience of maturity. But is it true? Does this phrase carry a dangerous note of swamp stagnation? Is it possible to call a man who has no faith in progress and change a human being?

God created man perfect, endowed him with the creative ability to transform himself and the world around him. So there is always a chance for change for everyone. God gives a human being a part of earthly life just for creation, during which it is necessary to cultivate the best of all virtues and to get rid of the ballast of sin. The finale of Lent is the resurrection of the dead for future life. For a life where the true currency is the accumulation of the soul. Mary of Egypt went into the desert to die and be reborn for eternity. The resurrection of her memory is a reminder that life is not meant for entertainment and consumption. Life is our bridge to eternal happiness.

Vladimir Basenkov