When the Old Believer Soloviev family began to use the surname Simon, Fr. Pimen himself can’t remember. Neither did his father—Evstathy. On the other hand, Fr. Pimen well remembers that he and his matushka Maria and their children and grandchildren have gone to the Church of the Nativity of Christ their entire lives, in Erie, Pennsylvania, on the banks of the Great Lake of the same name.

The parish of the Nativity of Christ Church was founded in 1916 by Russian Old Believer immigrants who arrived to the United States in the second half of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

“The founders of our parish—bespopovtsy-Pomorians[1]—came from the Pskov region and Novgorod and fled to the western edge of Russia, to the area between the cities of Suvalki and Senia, on the territory of modern Poland, in the eighteenth century due to persecution,” says the rector of the church Archpriest Pimen Simon. “And from there they began to immigrate to the U.S. in the late 1880s.”

Many of the Old Believers who came to America settled in Erie, where at that time you could find work in paper mills and on the docks on the waterfront of Lake Erie, to the north of the current location of the church, and also in the mines and steel mills of Pittsburgh and the surrounding cities in Pennsylvania.

By 1916, so many Old Believer families had settled in this area that the leaders of the community decided to build a church. The first church, built in 1919, was dedicated in honor of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos, and the first nastavnik was Nikon Pantsirev—he accepted the role of spiritual leader of the community in 1923.

In the early years of the parish, the Old Believer traditions remained intact, and the members of the community preserved the Russian language. However, after the Second World War, there was an “Americanization” of the parish. The men began to shave their beards, the women—to cut their hair, and later they stopped wearing the traditional colorful sundresses. The children began to speak mainly English.

“During the Great Depression, many Old Believers went to Detroit, where they hoped to find work,” continues Fr. Pimen. “In the early 1960s, the Tolstoy Fund found money and ‘extracted’ Old Believers from Turkey to the U.S. who had gone there from China, which was becoming communist. The largest group of Old Believers settled in New Jersey, but many considered these places too Americanized and moved to Oregon, and others even farther—to Alaska, where they founded their own city, Nikolaevsk, in 1968. The community in Alaska is the largest and most developing today due to the preservation of the traditions and family life. They live separately there, like their counterparts in Siberia. Small groups of Old Believers in Alaska recognized the priesthood but are not in communion with the Orthodox throughout the whole world and do not recognize the Russian Orthodox Church.”

The majority of the Old Believer communities in the U.S. are small: The parish in Detroit only serves Vigil occasionally, and there are almost no services in Millville, New Jersey. With the Old Believers who broke away from our community, whose church is a block away, the 105-year-old nastavnik also rarely does the services.

The Nativity of Christ Church celebrated its 100th anniversary this year. The celebration of the jubilee was led by the First Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad Metropolitan Hilarion of Eastern America and New York.

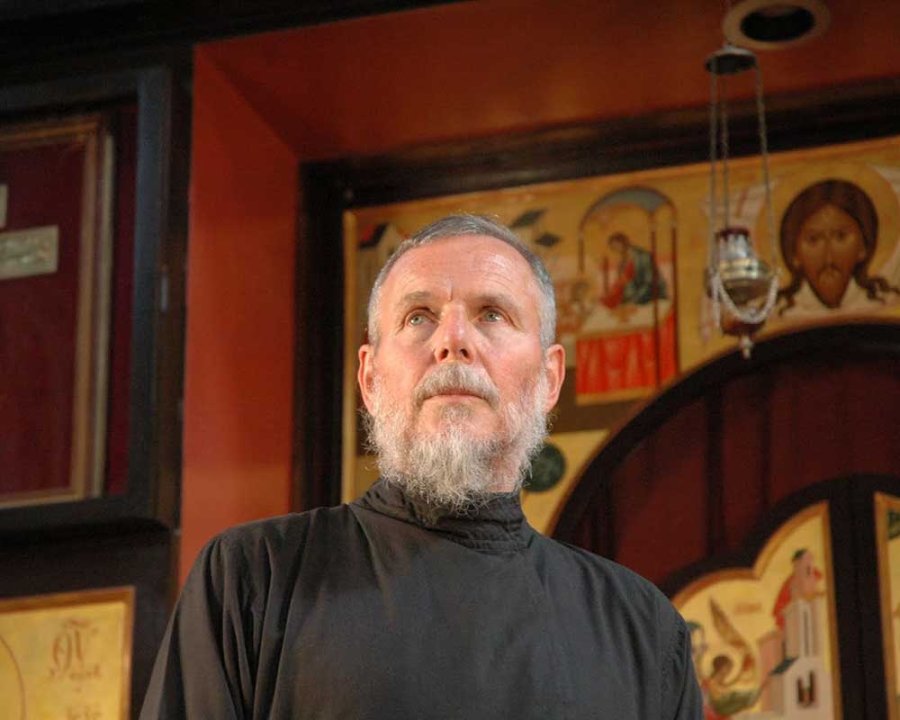

When people first come to the church, they are struck by the extraordinary beauty inside with the splendor of the icons and paintings. Almost all of them were painted by parish priest Archpriest Theodore Jurewicz.

“In 1976, when I became the nastavnik of what was still a priestless Old Believer community at the time, I realized the parish would diminish over time,” recalls Fr. Pimen. “The third generation is no longer very devoted to the Church. At that point we had 400 parishioners, and earlier we had up to 600, but many came just on Nativity and Pascha. They considered themselves strict bespopovtsy, but didn’t keep the fasts.

At that point we had 400 parishioners, and earlier we had up to 600, but many came just on Nativity and Pascha. They considered themselves strict bespopovtsy, but didn’t keep the fasts.

“Now we have a stable 175-200 parishioners, the majority of which regularly come to church. There are many converts.

“The parish has a Sunday School with the children learning the Law of God and Znamenny singing. I would like if some of the youth would study Church Slavonic, which we use together with English in the services.”

One of the regular young parishioners is Brandon Mathers, an engineer. We met in the city early Saturday morning, on the eve of the Nativity of Christ Church’s patronal feast. He made the two-hour drive from Pittsburgh, and I—eight hours from New York to make it to the festal services.

Brandon first encountered the Orthodox Church at his friends’ wedding, almost three years ago when he was studying in college; he was a Catholic at that time. The Orthodox services immediately attracted him. After college, he worked in Tennessee where he went to a parish of the Orthodox Church in America, and after a thirteen-month catechumenate he received Orthodoxy. Having returned to Pittsburgh, he met a family that went to the services in Erie, and so he went to the Old Believer church for the first time.

Brandon has been going there on Sundays and feast days for almost two years now. He has grown a beard and wears an Old Believer embroidered shirt. He likes the Old Believers’ adherence to the traditions of the services, the fullness of the All-Night Vigil, the order, the melodious chants, and the warmth of hospitality of his spiritual friends. He doesn’t presume, but hopes to find an Orthodox wife for himself.

Today, the majority of Old Believers wear modern clothing in their everyday lives, and on Sundays and feast days the men wear a sectioned shirt embroidered at the collar in church. The women wear a white handkerchief in church, and in Erie the parishioners no longer pin it in front, but simply tie it, like Orthodox women in Russia.

It’s become a new phenomenon in the communities for the youth to marry people of other faiths and nationalities. The young people themselves choose their other half; the parents do not interfere in this process, and the age of marriage is increasing, both for the young women and young men. The majority of Americans who marry Old Believers accept their faith.

—In your view, what is the purpose and mission of the Old Rite in the modern world?

—We are not a museum showpiece in the modern world. The way we serve is our means of communicating with God. We use English instead of Slavonic, and that is also part of the means of communicating with God. When I became the nastavnik in 1976, I wasn’t planning to do the services in English. But time goes on, and our parishioners change.

We use English instead of Slavonic, and that is also part of the means of communicating with God. When I became the nastavnik in 1976, I wasn’t planning to do the services in English. But time goes on, and our parishioners change.

The young families said they don’t understand the Slavonic services so they didn’t want to go to church. It was very painful for me to switch to English. This was in 1979. It nearly started a war in the parish. Many people said to me: “How can you allow yourself to do this?” They called me, “Terrible Pimen.” We met and discussed it several times, and the main thing was to keep the parish viable. But without transitioning to English as the main language of the services, and then the restoration of the priesthood and a return to the full practice of the Sacraments and rites, we wouldn’t be able to exist.

Finally, after much discussion and reflection, it was decided that the parish had to gradually introduce English as a liturgical language. In 1980, beginning with the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, we began to do the services with a small amount of English.

The young families said they don’t understand the Slavonic services so they didn’t want to go to church.

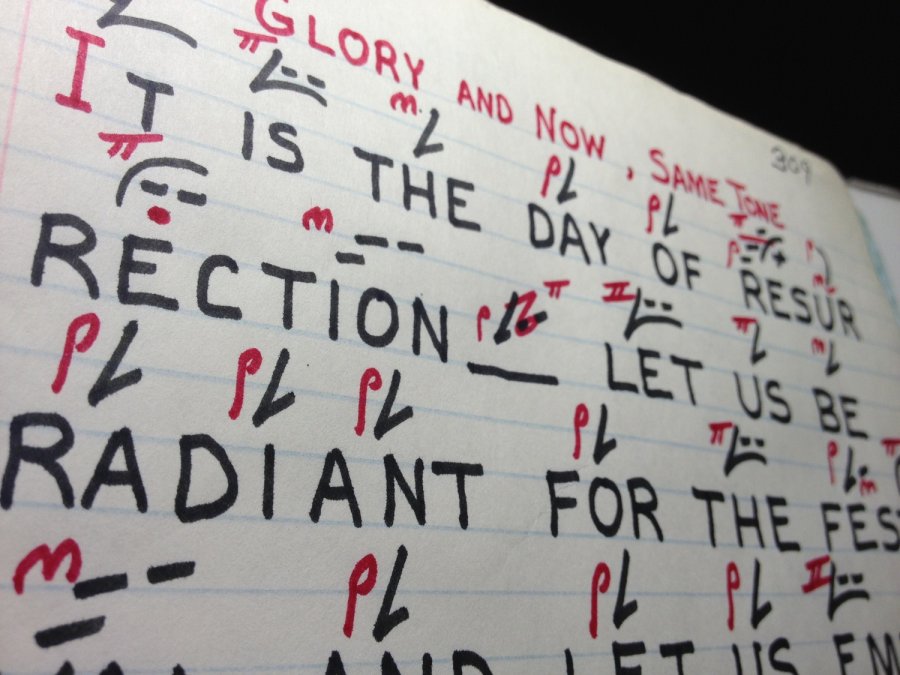

But we needed translations of the liturgical texts, and here Fr. German (Ciuba) helped us. Now Old Believers use his translation of the prayer book in both Americas, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and the countries of Southeast Asia. Commentary on the Sacred Scriptures, the Octoechos, the Torzhestvennik, the Festal Menaion, and the majority of the Lenten and Paschal Triodion have also been translated.

But translations are only part of what we needed. We couldn’t do without arranging the English texts of the hymns for the ancient Znamenny chant. My brother, Deacon Mitrophan, took on this task. He arranged many of the hymns, adapting them to English as they would sound in Church Slavonic.

An even more controversial decision came two years later. After a careful study of the schism in the Russian Orthodox Church in the seventeenth century and the subsequent loss of the priesthood and reading the works of the Holy Fathers, Fr. Pimen came to the conclusion that the parish should do everything possible to reunite with the fullness of the Orthodox Church, to have a bishop and priest in the parish. In 1982, a small research committee was formed, as a result of which, on January 9, 1983, a parish-wide vote was held. About eighty percent of the parish voted for unification with the Russian Church Abroad.

In 1982, a small research committee was formed, as a result of which, on January 9, 1983, a parish-wide vote was held. About eighty percent of the parish voted for unification with the Russian Church Abroad.

—When I first thought about our community becoming popovtsi (Edinovertsi), I went to Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville to investigate how serious the “Nikonians” were about receiving us and respecting the Old Rite. I met a hieromonk there—Fr. Hilarion (today Metropolitan Hilarion, the First Hierarch of ROCOR). I sat with him near the monastery church. He spoke with me with such love and respect that I thought there was a real chance at reconciliation.

In 1981, we went on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and during the service in the Ascension Monastery on the Mt. of Olives, it became completely clear to me that we had to restore the fullness of communion with the Orthodox Church.

It became completely clear to me that we had to restore the fullness of communion with the Orthodox Church.

In the fall of 1982, when our research committee was finishing its work, we decided to go under the omophorion of the Russian Church Abroad.

On July 24, 1983, Fr. Pimen was ordained as a priest by Archbishop Laurus (Škurla; later the Metropolitan, † 2008), and the Church of the Nativity of Christ was finally consecrated. During the Dormition Fast in 1983, Fr. Pimen baptized more than 500 parishioners.

In 1984, the world-famous iconographer Fr. Theodore Jurewicz joined the parish and continued beautifying the church, painting many icons.

—The restoration of the priesthood and the transition to ROCOR was a very difficult task. I knew that many from our parish were ready to kill me. About a quarter of the parish left us. When they started serving (a block away from us), I would weep during the Liturgy because I had lost them.

I knew that many from our parish were ready to kill me. About a quarter of the parish left us. When they started serving (a block away from us), I would weep during the Liturgy because I had lost them.

—Fr. Pimen, what do you value in your parishioners?

—We have a tight-knit community, united by devotion to the faith and the parish. Throughout all these years, the people have tried to keep the commandments that the Savior gave us.

Unfortunately, we are, with few exceptions, not Russians, and our parish can no longer be called a Russian Orthodox parish. The majority of Russians in Erie are Baptists or Pentecostals—Fr. Pimen says with sorrow—and that’s despite the fact that the clergy and parishioners are very hospitable to one another and to newcomers.

Russian-speaking people still come now, but they light a candle, kiss an icon, and leave. They come to baptize their child, and I ask: “Where are you from?” “Erie.” “How many years have you been living here?” “Three years.” So why didn’t I see them all that time? I ask them to come to Liturgy for four weeks. They leave, and I never see them again.

On the other hand, Ethiopians and Indians come to us. We have Italians, Germans, Poles, Irish, and French at our parish who have received Orthodoxy.

I ask my parishioners: Who are we? We are Americans of the Orthodox faith, serving according to the Old Rite. Some people come here and hope to see the same kind of Old Believers who live in isolation in Siberia. But we are Americans, and we don’t pretend to be anything else, we don’t adjust for the Russians. And if we weren’t who we are, we certainly wouldn’t have survived in our times, especially in a place like Erie. It’s not New York or Washington. There aren’t many Russian-speaking immigrants here, and if we’re not open to people of other nationalities, we will cease to exist.

Our parishioners are much more responsive and loyal than those who have come to our city lately from the countries of the former Soviet Union. There was a time when our church was surrounded by unsightly buildings. We had begun to take care of the internal beautification and splendor of our church and didn’t want the church to be in such a terrible environment. I appealed to our parishioners with a request to help the church buy these houses and put them in order. Within three weeks the people had collected $500,000. All in all, we spent $900,000 to repair these houses.

Our parishioners showed the same devotion when there was a fire in the church. On July 22, 1986, in the afternoon, as the parish was preparing to receive participants in a conference it was hosting, smoke started billowing from an opening in the ceiling above the choir.

After several hours of fighting the fire, everyone was surprised to find that the Royal Doors and deacons’ doors, the iconostasis, icons, books, altar, and vestments in it miraculously remained undamaged. The new church was completed by the following summer.

—Fr. Pimen, tell us about your family.

—I have a wonderful family. My wife is Mary, of Irish descent. She was Catholic, and was baptized Orthodox in honor of St. Mary Magdalene. We have an interesting tradition in the Old Rite. The only woman known as “Maria” is the Mother of God. The rest are Mary. Thus, my Mary, disappointed with Catholicism, started coming to our church while studying in college. Our parish was priestless at that time. I knew her from church. Then I left for college and I was gone for four years. Mary went to church this whole time. My father asked me: “Why aren’t you married?” And soon we got married.

We have three children: Daria, John, Katerina. We were lucky with them: They never said they didn’t want to go to church and they are all still active in the parish, spending a lot of time in the church, and helping with absolutely everything, from singing on the kliros, to the parish website, to social work. At the same time, they all have secular jobs. Daria is the CEO of a company, John is the director of communications for a large insurance company, and Katerina teaches for an online college.

We have four grandchildren. The oldest sings on the kliros and reads. Our youngest grandson, Joshua, really loves church and always serves during the services. He could even stand through a four-hour service when he was four years old.

Old Believer children generally behave exemplarily in church. If to characterize the behavior of both adult parishioners and children in an Old Believer church, in a word—order. It is unacceptable for us for children to run around the church during the services, screaming. On the other hand, we perhaps lose newly-arriving Russian-speakers because of this. They think Old Believers are a fanatical people.

I remember from childhood, when I was ten—we were priestless at that time—we would serve Vespers on the eve of Pascha. We began at 3:00 PM and served until 5:30. Then we served Compline with the rite of the burial of the shroud until 8:00. Then we read the long canon and finished the service at 3:30 AM. I remember I would stand without sitting until early morning.

I’m a happy man, and one of the reasons is that my entire family is active in church. I was brought up prudently, and I relate to my children and grandchildren the same way.

My children spend Saturday evenings and Sundays in church. Before that we play golf, go to the movies. On Sunday, when the Liturgy ends, I often go shopping or to the lake with my grandkids. They don’t address me in English, but call me “Deda” [“Grandpa”—Trans.].

If you ask me what worries me most in life, I would say it’s that this church would continue to live for many years and serve future generations. The church is the heart of my life. That’s how it’s always been. After finishing law school in Pittsburgh, I returned to Erie because of the church. My daughter Daria’s husband is a lawyer. They were both offered work in Pittsburgh, with a salary three times higher than in our city. But they gave it up and also returned here—because of the church.

A significant event for our parish was the consecration on August 14, 1988 of Fr. Dmitry (Alexandrov) as a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad specifically for the Old Believers, tonsured into monasticism the night before with the name Daniel.

A significant event for our parish was the consecration on August 14, 1988 of Fr. Dmitry (Alexandrov) as a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad specifically for the Old Believers, tonsured into monasticism the night before with the name Daniel.

—Fr. Pimen, how would you define the role of Bishop Daniel for your parish and Old Believers in America as a whole?

—Vladyka Daniel’s main role was in “guarding” the Old Believers’ liturgical practices. Although he himself was not an Old Believer, he felt how important it was for the Church to preserve the Old Rite. Vladyka would say: “Your ancestors died to preserve these services, ancient chants, and their melodies. As it’s written in the books, so you serve. What you have is unique, and you should preserve it. If someone doesn’t want to, they can leave, but nothing needs to be changed.”

Vladyka would say: “Your ancestors died to preserve these services, ancient chants, and their melodies. As it’s written in the books, so you serve. What you have is unique, and you should preserve it. If someone doesn’t want to, they can leave, but nothing needs to be changed.”

Even before his episcopacy, Vladyka was a very versatile man. He was a remarkable architect and iconographer, and a man of great spirituality and prayer. He also loved sailing. Many years ago, when he moved to Erie, he even built a boat that he intended to go sailing on. He had a great interest in cannons and weapons. He had a cannon at his house and he would shoot it on July 4, on Independence Day. He knew many kinds of chant—Kievan, Znamenny, Romanian, Byzantine; he spoke many languages.

He really was an outstanding man of the Church. Unfortunately, when Vladyka Daniel became a bishop, he was already very sick.

—Fr. Pimen, how do you see the future of the parish?

—It will be difficult, for a number of reasons. First: the growing secularization of society, and we, as part of American society, are subject to this secularization. Second: We are a very small minority. Third: We are no longer a Russian community and Russians will no longer come here for the most part, especially if they are not rooted in the faith.

The biggest problem is that our children with higher education cannot find work in Erie. If my own children or grandchildren can leave in the future, how can I ask other parishioners to stay?

When I was a lawyer and not yet a nastavnik, the situation in the parish was difficult; but I knew that if we didn’t begin to serve in English and didn’t receive the priesthood, then by the time I was 50-55, the parish would die. Nevertheless, we chose correctly, and our parish is growing and developing.

I knew that if we didn’t begin to serve in English and didn’t receive the priesthood, then by the time I was 50-55, the parish would die.

Right now we have about 100-150 parishioners. Ten or fifteen years ago, we had about twenty-five funerals a year, and now we have an average of five, while at the same time we get about five new parishioners a year. People come, they like the services. I’m in favor of our young people bringing their significant others to church. So the parish is stable now. Of course, we won’t have 400 people like before, but the parish will live.

We understand that the main purpose of the Church and parish is the salvation of the soul. At the same time, we participate and engage in various social programs. I myself participate in various organizations and groups of our region and city.

Every year, four or five churches in our city give their parish premises for homeless people to stay there for two weeks before and after Western Christmas. Every day during this time, our parishioners work with the homeless in shifts: 7:00-11:00 at night, 11:00-3:00 in the afternoon, and 3:00-7:00 in in the evening. We lay out mats in our church center’s sports hall and we cook breakfast and lunch for the homeless. The homeless shelter is run by my youngest daughter Katerina.

Every Friday and on Western Christmas we work in a soup kitchen for the poor, which is sponsored by the Benedictines. On Western Christmas we also deliver baskets with groceries to forty-sixty families, so they’ll have enough food for the feast. We have a food bank, and we deliver food to the needy every week.

During the Nativity Fast, we have a Christmas party for about 150 needy people, the majority of whom are from homeless families who have nothing; therefore we try to give them something during Western Christmas.

We have the project of Matthew Gregorov, “Shoe Tree,” in which we buy shoes for needy students.

We make sure that the state of our region doesn’t deteriorate, so it doesn’t degenerate. We try to the clean the area of slums, we buy houses and repair and restore them, and we build new buildings. We want our church to be in a safe environment. It’s important for us to keep the area clean and tidy.

The church and all this property belong to the parish. The parish chooses the priest itself, so our labors will not be lost.

—And how has your area and Erie as a whole changed in the last, let’s say, forty years?

—Erie is a rust belt city, which also includes cities in Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Forty years ago it was an ugly, dirty city. Such cities had to either transform or die. Erie began to transform, and today it is a dynamic city: Instead of paper manufacturing and shipbuilding, we have large high-tech companies, and insurance and tourist companies, where our young people work.

Everyone in Erie knows our church with the golden domes in the bay front area on the shore of Lake Erie. I already knew when I was studying in school that this church was a unique place, that there is something special in it. It absolutely must be preserved, and this is the work of the youth.

I tell the youth: I’m not some freak who knows nothing about the modern world. I played sports for many years when I was young: track, polo, baseball. I dated girls. And I went to church. When I had a legal practice, I also went to church. When I became the nastavnik, I would wear the embroidered shirt instead of a suit and go to church. So don’t say you have work and other things to do.

To this day I love to read and I try to keep track of what’s going on in the world. My homilies are often connected with current events, and I refer to what I read in the New York Times or Time Magazine.

I work with a group of 20 and 21-year-olds. I tell them to get an education, come back, find a spouse in church, get married, give birth to three children, and the parish will live!

"The way we serve is our means of communicating with God". by Tatiana Veselkina. Photos belong to the author.